This blog post gathers some of the experiences and conversations from the initial dissemination of Genomic Gastronomy’s “Terroir That Travels” project in Lautrec, France which was organized and hosted by Camille Pelissou, and features the story of Pink Garlic, a PGI from the region.

TERROIR THAT TRAVELS (TTT) uses maps and stories to ask how agricultural products and taste of place will migrate due to climate change.

The following field notes were collected by Camille:

Context

TERROIR THAT TRAVELS was shown in Lautrec on December 20th and 27th at the weekly market. We were given a spot at the market by the municipality and were able to show the project to some local residents: inhabitants of Lautrec, local farmers and merchants.

The market takes place every Friday from 08:00 to 12:00. It is the ‘quiet’ season from December to March, as not many tourists visit the town. Even though the attendance at the market was lower than it would be in other parts of the year, we were able to share the project and talk to some of the attendees.

Material

The following material was used on both days:

• A suitcase

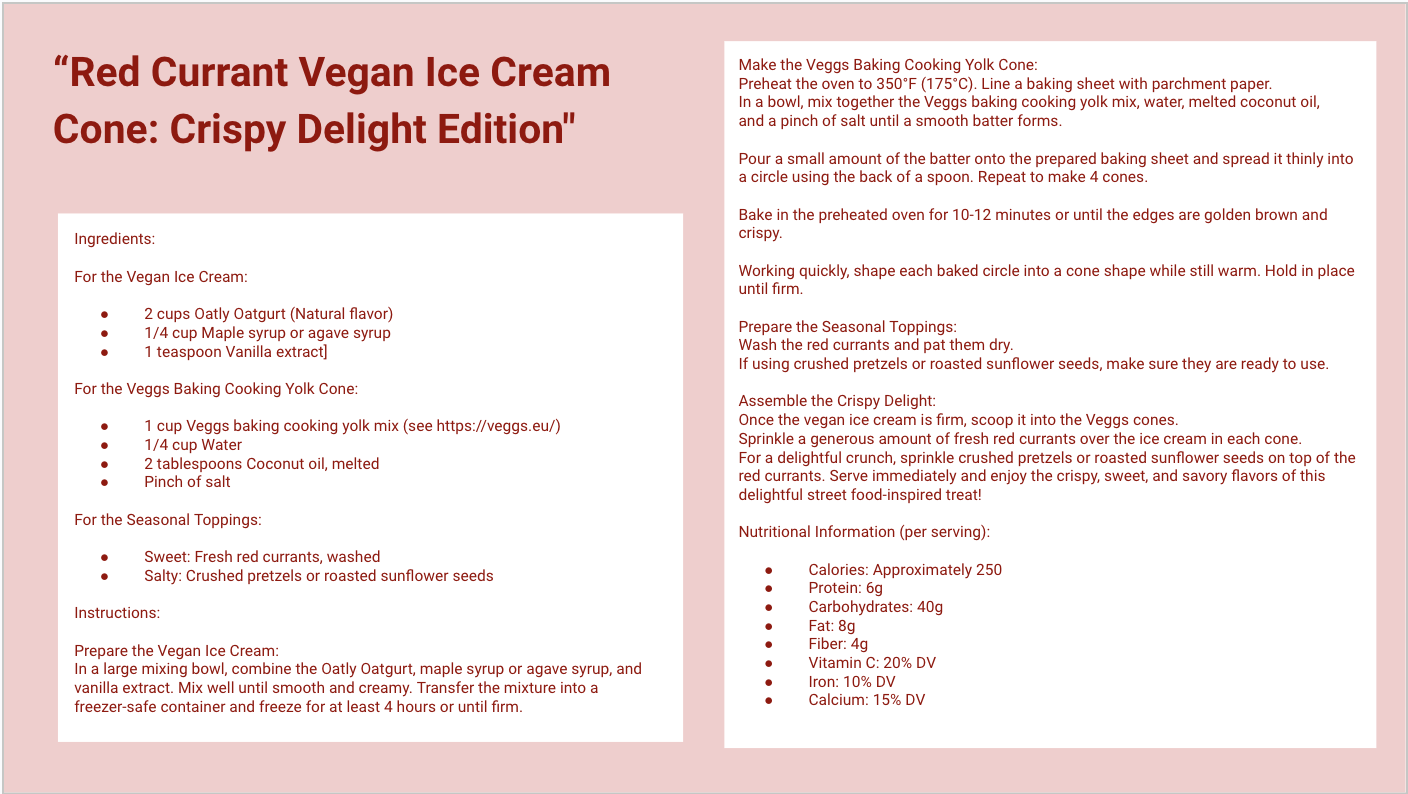

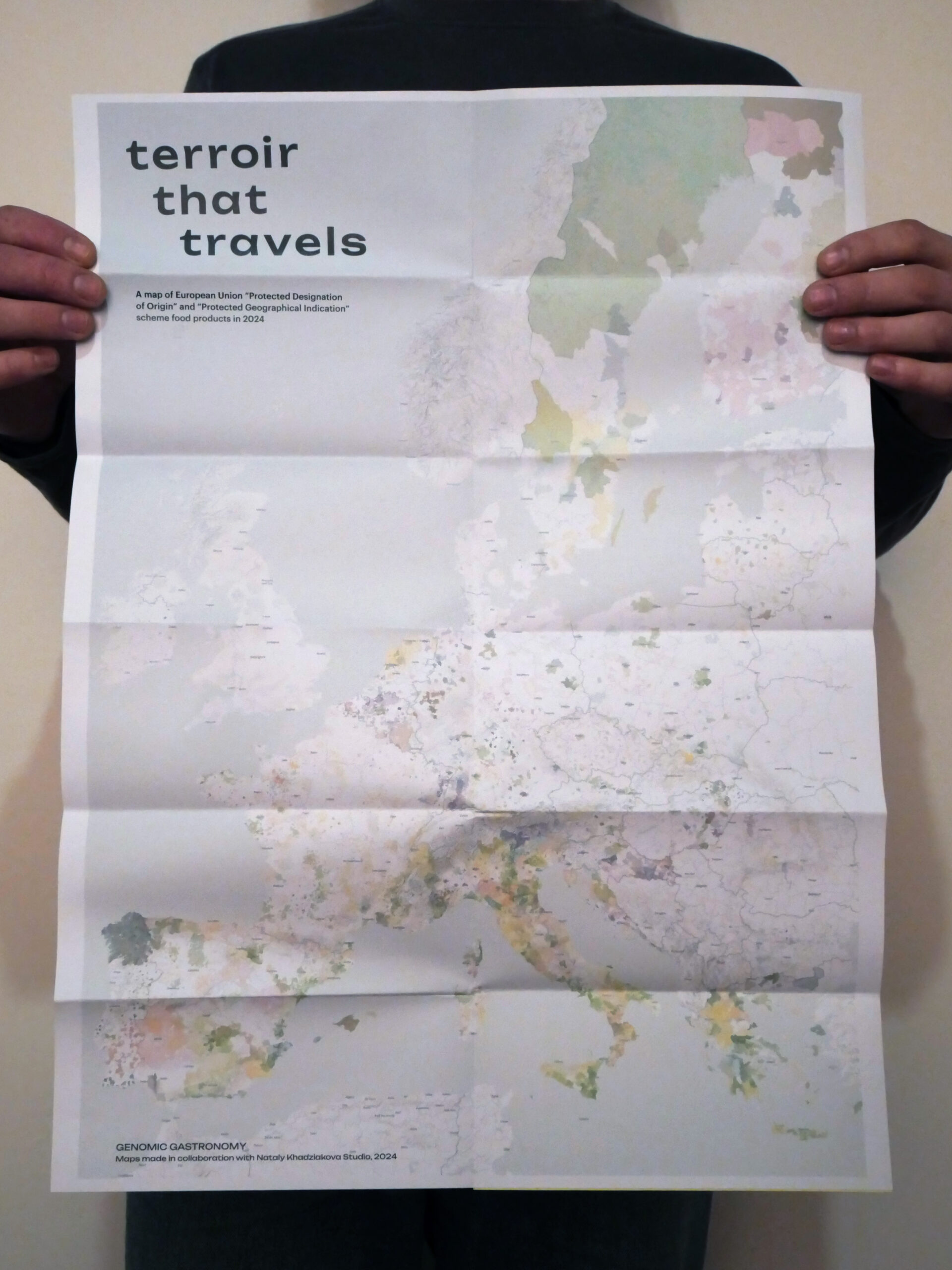

• 2 maps (one showing the PGIs areas in 2024 and one showing where the selected 3 PGI products might migrate in 2080);

• 3 viewmasters;

• 6 booklets (one for each PGI both in French and English);

• 1 bell;

• 1 set of headphones (connected via bluetooth to a phone);

• 2 pillows;

• 7 garlic crates (that once assembled were used as 1 table and 2 stools);

• 2 straps.

General notes

When I arrived in Lautrec on December 20th, around 07:30 AM, to set up TTT for the first time, people looked at me and I could hear them think ‘Who’s this person with the suitcase? We’ve never seen her on the market..?’. After introducing myself to all the other merchants, I collected their first impressions. Most of them were quite curious and intrigued about the project. Others did not really understand what the point was.

At first, people tended to be quite defensive (‘Who are YOU to talk about this issue?’) but once they heard that I was from the area, they loosened up a bit. Just like most families in Lautrec, mine has been growing garlic for generations. For this reason, people usually have a very strong emotional bond with pink garlic. The installation featured stories from three countries, but the story they were most interested to hear about was, of course, Pink Garlic. (In future versions of this project, we will continue to refine the ways that we tie the stories together and unify the shared concerns across geographies.)

The maps worked very well as a conversation starter. When people saw where their beloved product might migrate in the future, they showed signs of worry and it sparked their interest to hear more about the project.

(Above) The 2024 Map of European PDO and PGI products created by Genomic Gastronomy with Nataly Khadziakova Studio.

(Above) The 2080 Map showing a prediction of where three existing GI products could migrate, based on geographies that might have the necessary conditions for the product to survive. Created by Genomic Gastronomy with Nataly Khadziakova Studio.

QUESTIONING THE SYSTEM

Each farmer in the area has their own specific way of growing garlic. A lot of them question the cooperative system, especially the seeding system that they implemented years ago. If farmers join the cooperative, they have to use the certified bulbs that were chosen by the cooperative in order to grow big, pretty-looking garlic and have high yields. However, according to the farmers, these bulbs are often already contaminated with the pests and therefore rot very quickly. Therefore, some farmers decided to leave the cooperative and grow ancient varieties of garlic instead, which will grow smaller and have less yield but that can be kept for longer. According to farmers, these ancient varieties were also easier to digest because they were not treated with antigerminative products which in most cases make the garlic hard to digest.

ENVIRONMENTAL & LIVING COSTS

People are concerned by the use of pesticides. A visitor shared that he comes from a family of wheat farmers and that all of them have either Parkinson or Alzheimer. According to him, these two issues are related. He was also worried about the impoverishment of the soil. He said that nowadays if we don’t add agricultural inputs into the soil, it would be completely dead and nothing would grow. He assumed that this was because of years of pesticides and other chemicals use.

People are also concerned about suicides within the agricultural sector as they all know families affected by this issue. Farmers often end up being stuck within a system where they feel like they don’t have the choice: they have to invest in very big infrastructures in order to follow up with an economic dynamic that only encourages profit and growth. They end up borrowing money from banks and paying back huge loans but if their harvest is bad for a few years in a row, they cannot pay back the banks.

DIFFERENT PRODUCTS, SAME ISSUES

One of the merchants who was selling vanilla from Madagascar on the market came to experience the project. She reflected on how the challenges that pink garlic is facing are similar to the ones Vanilla is facing in Madagascar. Madagascar’s vanilla crops are highly vulnerable to climate change, as they require specific temperature and humidity levels.

In the last few years, more and more extreme weather events such as droughts and storms have hit the island. These conditions often devastate harvests, deepening the economic challenges faced by Madagascan producers. Just like pink garlic in Lautrec, to secure the future of its vanilla industry, Madagascar needs a multifaceted approach that includes continued investment in sustainable farming practices, infrastructure improvements, and technological innovation.

Around the end of the market, I went to buy some cheese at the cheese stand and I noticed that some of them were labelled ‘thermised milk’. As I was unfamiliar with this label, I asked the cheese merchant what it meant. Here is what he told me: around 20 years ago, farmers heard that the European Union wanted to ban raw milk from cheese making practices because of sanitary reasons. Therefore, they decided to come up with a new kind of milk to counter the law: thermised milk. This is an alternative product that stands in between raw milk (which is not heated up) and pasteurized milk (that is brought to a 90°C boil to get rid of most bacteria present in the milk). Thermised milk is brought to a 60°C boil to remove some of the bacteria, but not all. By doing so, the farmers could preserve a taste that was similar to raw milk cheese while preventing the presence of most bacteria.

(EDITOR’S NOTE: The contestation around Raw Milk is something CGG has following since way back in Food Phreaking #00. It is interesting as an “indicator species” of food system perspectives.)

WHAT ABOUT THE NEXT GENERATION?

A lamb breeder who experienced the project shared that her biggest challenge was to anticipate how the next generation will be able to farm. According to her, meat has bad press, especially in the eyes of the new generation, and it is very difficult to see a future for this kind of farming. Indeed, her son is not willing to take over the farm.

Moreover, although she is passionate about her job, her business is almost not viable economically. All these reasons pushed her to stop her farming activity in 2025. Instead, she is now considering planting Mediterranean trees such as almond and pistachio trees as they should be able to grow well in the region according to climate predictions. But growing trees takes time and that is something that only the next generation (her son) will be able to profit from. She is now struggling to find an alternative activity that she could do in the meantime, to sustain herself.

UNINFORMED CONSUMERS

A lot of farmers I talked with were concerned about the lack of knowledge that people have about the products they consume. For instance, with pink garlic a lot of consumers think that when a garlic clove starts sprouting, it is not edible anymore and they throw it away. However, the farmers see this as a good sign showing that the product is alive and hasn’t received an anti-germination treatment.

The prices between GPI certified garlic and uncertified garlic are not that different (14€/kilo for certified garlic VS 12€/kilo for uncertified). When asked about this difference, the farmer answered: “The certified garlic needs to be more expensive for the tourists, we need to be able to justify the quality of the product by raising its price”.