From November 21-26, 2021, we visited the Veluwe region of the Netherlands for our first research trip for our STARTS4Water residency in collaboration with V2_. During the week we explored the local culinary scene, biked the Hoge Veluwe National Park, and visited regional museums which cover the topics of geology, biology, and water. A highlight of the trip was our visit to the Ketelbroek food forest with Wouter van Eck.

KETELBROEK FOOD FOREST: OVERVIEW

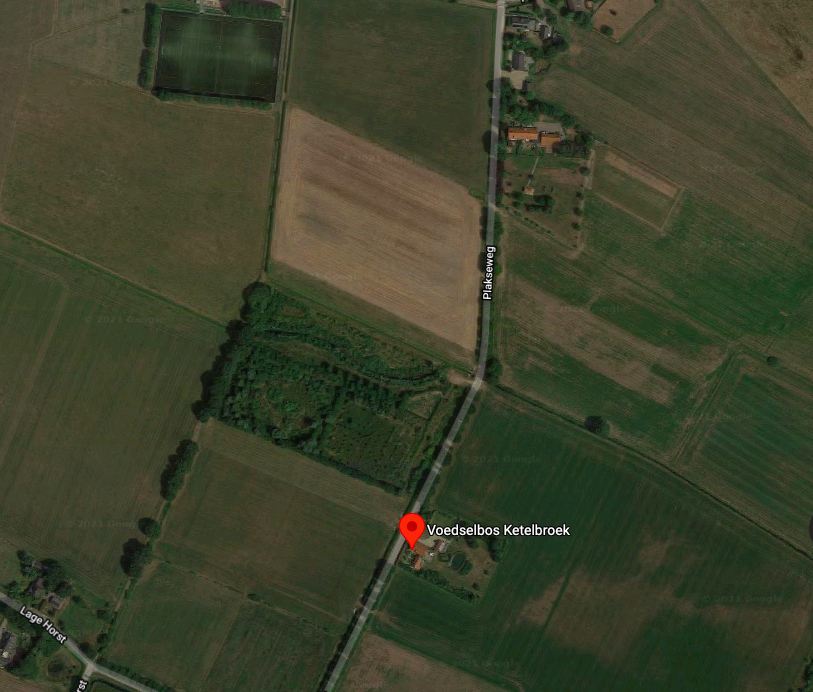

The Ketelbroek food forest is located in Groesbeek, a little south of the Veluwe region in the Gelderland province. The Food Forest was started in 2009 by Wouter van Eck and Pieter Jansen and now contains 32 food-producing species of plants on its 2.5 hectares (6 acres) of land.

Surrounded by monocropped fields containing plants like corn for animal feed and rye, Ketelbroek food forest has a significant visual impact and ecosystem service impact. About a kilometer away, there is a heavily managed natural preserve, so the location of the food forest, situated between these two different landscapes (agricultural field and forest preserve), has made studying the biodiversity and water retention impacts of the food forest possible.

For example, the food forest has equivalent or higher counts of nesting birds, butterflies, and ground beetles. In 2016 when heavy rains struck, the food forest absorbed water and avoided major flooding while the neighboring fields were inundated and suffered greatly. During a drought in 2018, the surrounding fields were completely brown or required heavy watering while the food forest remained stable. Additionally, the food forest fixes more carbon annually than a field of crops on the same size plot.

FOOD FOREST PLANNING & MANAGEMENT

Wouter, our kind and knowledgeable host at the food forest likes to let the food forest manage itself as much as possible. He explained on a pre-visit video call that the goal was to let the forest behave, grow and cycle like any other “natural forest” would. The food forest is a “polyculture of perennial, woody species” that uses ecological principles to avoid the need for external inputs like fertilizer or pesticides.

During our conversation, it became clear that the hard work Wouter does for the food forest probably happens before planting and/or outside of the food forest itself. Ketelbroek is a USDA hardiness zone 7a, meaning it gets fairly cold in the winter. To create a resilient forest, Wouter sourced plants and trees from various geographies—worldwide—that have similar climates to the Netherlands. In fact, out of 32 species, only two (chestnut and stinging nettles) are native to the area. The rest are either commonly grown non-natives, or specially selected varieties that thrive in Ketelbroek’s conditions.

Although at first the forest appears to be sprouting in all directions, the construction plan of the food forest has been meticulously considered. Indeed, nothing – or almost – is placed randomly. While the hedges act as windbreaks and bird sanctuaries, the second row of trees, generally smaller, benefit from this protection from the wind but also from the shade created by the first row of trees. This way, each tree is given a spot that fulfills all its needs.

AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY, DATABASES OF TASTE & LAZY FARMING

The selection of trees includes fruit trees like peach, pawpaw, Japanese plums, and kaki, and nut trees like chestnut, hazelnut, walnut, heartnut, and hickory. Other edibles include gooseberry, Nanking cherry, and Siberian peatree.

As our visit was in November, the food forest was somewhat dormant, re-energizing itself for spring, however even on that cold rainy day, we were able to taste a special Russian variety of kaki (persimmon), tongue-tingling sichuan peppers off the tree, and the caramel-like treat known as pheasant berry. Wouter partners with a chef on a project called “Botanical Gastronomy” to experiment in the kitchen with the unusual varieties (in the Netherlands) of plants grown in the food forest.

Wouter shared with us an inspiring moment he faced during his first years of working on the food forest: a caterpillar invasion. After considering using Green Soap (an non-toxic product originally made out of hemp oil for household cleaning) to get rid off them, he finally decided not to do anything, as his instinct of “lazy farmer” (as he likes to call himself) was telling him to do. A few weeks later, Wouter happily found out that the caterpillars were gone, eaten by a new species of bird who decided to nest in the food forest. “Sometimes, you should just let nature do it”.

While the Ketelbroek food forest contributes to biodiversity, water retention (draught/flood tolerance), carbon fixing, and food production, it has also been used to push for policy changes and funding that legitimize this form of agriculture under Dutch law, and to normalize this in the “Green Deal” initiative in Europe.

THE LONG VIEW

Food forestry can require a kind of long-term thinking that most of us struggle with. Wouter will plant fast-growing trees to provide vegetation and maintain soil health for other trees that grow slower. For example, tree species that will live for only 10 or 20 years surround a Korean Pine Nut sapling that will grow slowly, living somewhere around 1200 years—carrying on the food forest long after we’re gone.