In September & October 2020, our studio conducted an internal master-class with Dr. Johnny Drain, guiding us through ways to further explore fermentation. We have been running separate experiments in our homes and our studios and below we will share the basic results here with you. Having members 6+ members of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy across the globe attending these workshops, we have been able to work with a wide variety of different raw materials for our fermentation experiments.

BITTER GOURDS, CHAYOTE & DRIED ANCHOVIES

Akash’s experimented with the local produce of Chennai had some exiting colors coming forth from the button mushrooms. After a few days the liquid turned a bright yellow color from the mushroom spores.

FIGS, PETINGA & LACINATO KALE

Working with different resources in our different parts of the world, we were keeping our eye out for what food resources were in abundance in the early autumn. Emma in Portugal experimented with figs, lacinato kale and brown button mushrooms that ended up in lacto-ferments and a surf & turf kimchi.

Experimenting with fermenting fish to garum, a months-long process, is not yet finished. In Portugal, you can go to streetmarkets where fresh ‘patinga’ (small fish) are auctioned off early in the morning among other resources. In ancient Greece and Rome, garum was a popular and widely used condiment, also referred to as liquamen.

Emmas fermented figs have been tasted and tried out as topping on pancakes with a dollop of yoghurt, and her mushroom fluids was turned into a tasty mayonnaise with recipe below.

Emmas’ Mushroom Mayonnaise:

- 1 egg (vegan: switch it out for ~45ml of aquafaba)

- 1 tbs lemon juice

- 2 tbs fluids of fermented mushrooms

- a splash of vinegar

- 2 cloves garlic

- 1 tsp mustard (optional)

- salt/pepper to taste

— blitz all and slowly add:

- ~3/4 cup olive oil (or until it reaches desired creamy consistency)

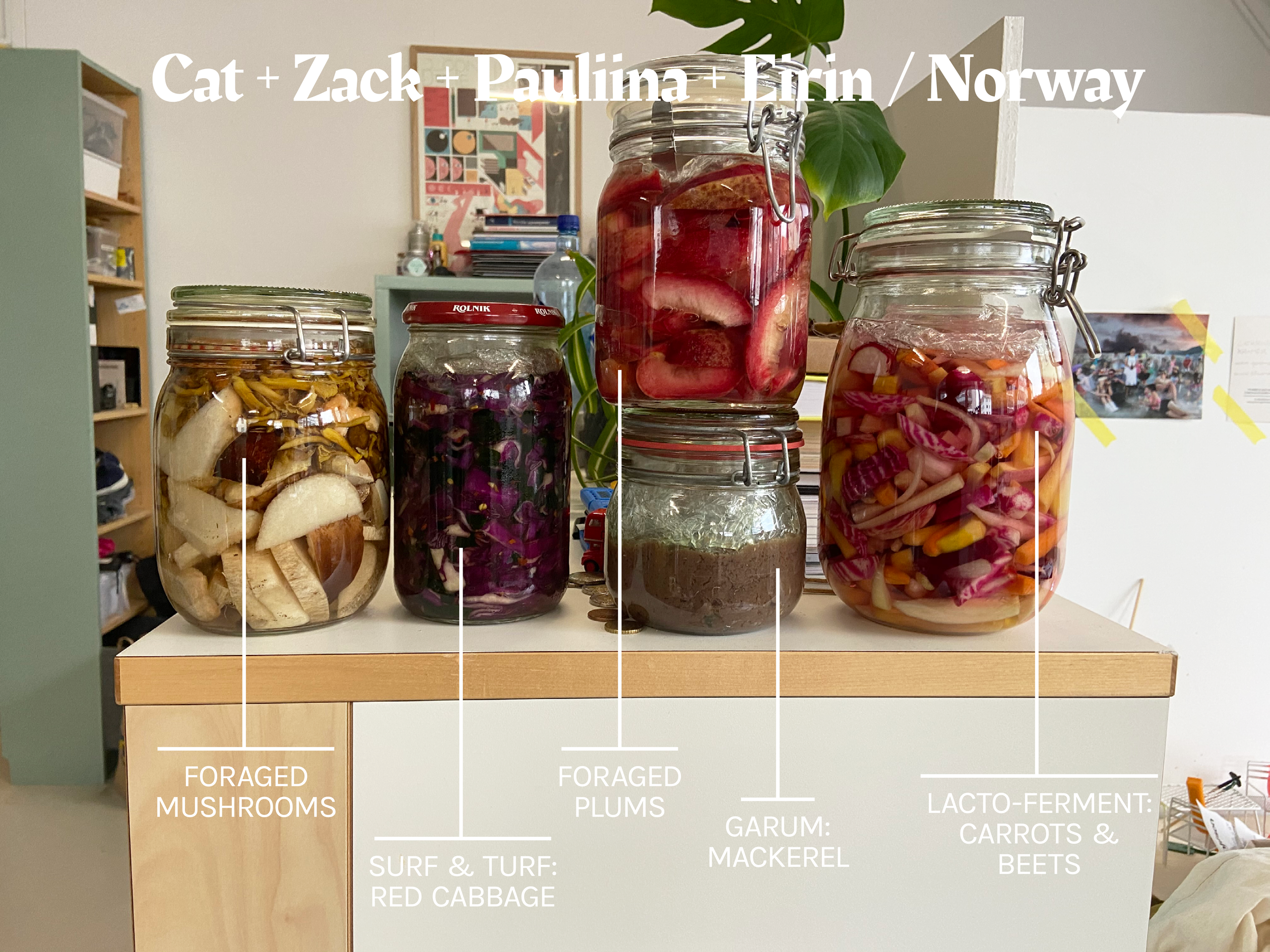

ROOTS, PLUMS & FORAGED MUSHROOMS

In Bergen, our studio members Cat and Zack, Pauliina and Eirin worked collectively and separately with fermenting abundance. They also experimented with making garum from locally sourced mackerel. Having an abundance in root-vegetables, they also worked with making vegan charcuterie, both with and without koji (Aspergillus oryzae).

Considering the cooking aspects of microbial experimenting, thinking and working with the texture and thickness of the different foods, we experienced how they reacted over time to the solutions we helped cook them in. The plums created a tasty liquid, but the flesh of the fruit broke down quite quickly, so we could consider how to texturally bring them to another level, maybe through dehydration, or simply as a purée.

We turned our vegan charcuterie drying process into a vegetable mobile twirling over our heads as we worked on our other projects, always reminding us of our microbial cooking to be eaten later.

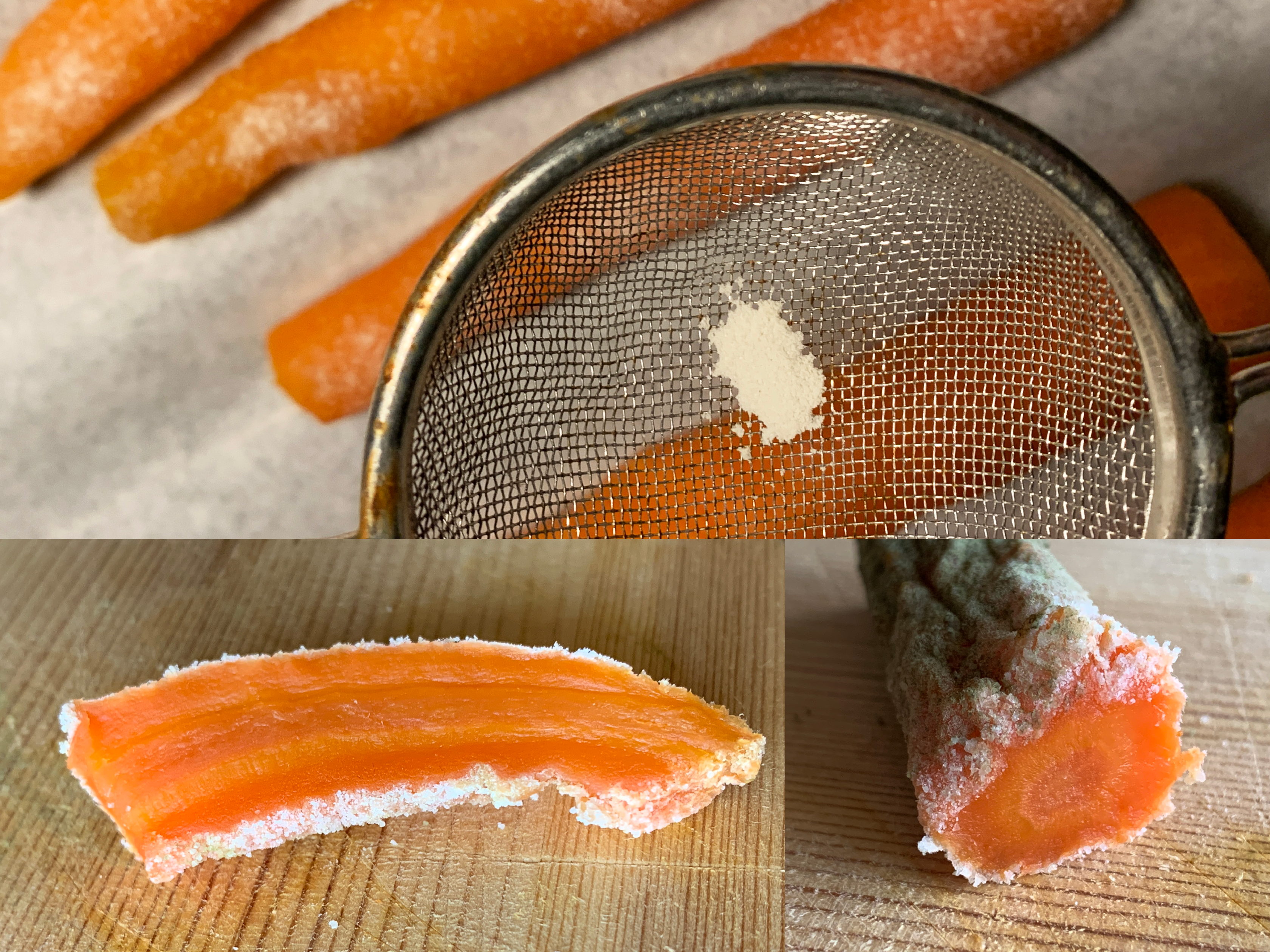

Studio-member Eirin experimented with vegan charcuterie with carrots inoculated with koji-spores, a friendly fungi developed over centuries in cooking culture in Japan. Keeping the good development of the inoculation was a challenge in a hacked breeding environment, and the koji ended up sporulating earlier than anticipated. However, the carrots turned out to a tasty treat — the carrots texture could be described as that of a dried apricot, but not as sticky, salty and with striking licorice notes in both texture and taste.

NEXT STEPS

Each member of the Center will likely continue to experiment with fermentation in their home kitchens, and the one technique that is likely to be revisited in a more rigorous way is the vegan charcuterie (with Koji spores) that we will likely use for either our Pantry of Protein Futures research or the Meatigation project we are a part of in Norway.