One of the Center’s mandates is to study the biotechnologies that make up human food systems. Cheese is one of the earliest, non-obvious and most widespread biotechnologies in use on the planet.

For the Planetary Sculpture Supper Club held in Portland, OR we served three regionally produced cheeses (based on our research from Cheese Wrestling.)

Each regional cheese had different combinations of [raw/pasteurized, rennet type, milk type].

Chevre Anise Lavender, Rollingstone (ID)

[pasteurized, vegetable rennet, goat milk]Smokey Blue, Rogue Creamery (OR)

[raw, vegetable enzymes, sheep milk]Seastack, Mt. Townsend Creamery (WA)

[pasteurized, animal rennet, cow milk]

One question we asked at the dinner was: In comparison to ubiquitous industrial cheeses in the United States (ex. Velveeta cheese) can these regional cheeses be classified as Appropriate (Bio)Technologies? Appropriate technologies have some or all of the following characteristics:

- small scale

- labor intensive

- energy efficient

- environmentally sound

- locally controlled

- people-centered

We asked our diners what they thought the advantages and disadvantages of privileging the above characteristics in a technology were. Some of the diners helped us define (as well as challenge the idea) that there are “inappropriate” technologies. Some diners were shocked that Genetically Engineered rennet is used in the industrial production of cheese in the U.S.

A few diners were keen on the idea that cheesemakers should be recognized and aknowledged as some of the worlds oldest biotechnologists. It was agreed that with such a long history and diverse body of knowledge, cheese makers should explicitly be included and invited to conversations about biotechnology, ethics and sustainability. If biotechnology for food system resilience is the question, regional cheese production may be part of the answer. (And it certainly tastes better than Velveeta. And taste matters.)

Explicitly naming cheese production a “biotechnology” and comparing it to the range of other biotechnologies and controversies surrounding food is one way the Center has tried to open up a space for eaters to taste and talk about difficult topics. Controversies in cheese making include: ongoing debates about pasteurized vs. raw milk cheeses, and the role of rennet.

GMO-Microbial rennet is used more often in industrial cheese-making because it is less expensive than animal rennet. Traditional cheeses from Europe must legally be made using rennet from animal stomachs. There are also cheese innovators that use vegetable-based rennet substitutes to create entirely new cheeses. Â Once you create a cheese plate with each of these kinds of cheeses, and explain the rationale for each kind of rennet, it is clear that the matter is much more complex than simply tradition vs. innovation.

Even the legal regimes for how cheeses are named are periodically contested. In 2002, the U.S. FDA issued a warning letter to Kraft that Velveeta was being sold with packaging that inaccurately described it as a “Pasteurized Process Cheese Spread.” Instead of complying with the label’s requirements, Kraft rechristened Velveeta “Pasteurized Prepared Cheese Product,” a term for which the FDA does not maintain a standard of identity.

The legal regime for cheese in the U.S. seems to do two things well: protecting the trademarks rights and proprietary processes of large industrial producers, and creating designations such as Pasteurized process cheese food that seek to protect consumers by explicitly stating the components and nutritional value of cheese, based on nutrition science and chemistry.

In the EU, the Protected Geographical Status tends to protect the rights of geographic and cultural traditions. If a cheesemaker wants to use the trademark name of a geographical indicators, they need to explicitly follow rules and processes that are available publicly here. So although some kinds of innovation are discouraged (most PDO protected cheeses require the use of animal rennet instead of vegetable rennet) the processes are public, and the naming conventions are based on the traditions of a geography and culture.

Also, because the U.S. does not follow this EU convention, it can sell commercially produced imitator cheeses such as “Parmesan” cheese instead of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. However, when American imitator cheeses are sold in Europe they need to have different names so Kraft’s “Parmesan Cheese” becomes “Pamesello Italiano”.

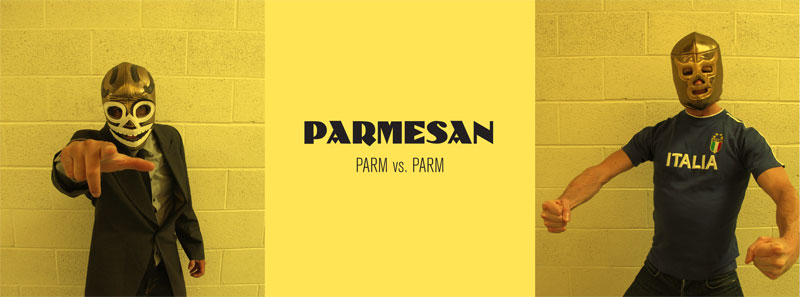

Kraft Parm vs. King Parm from Cheese Wrestling

In short:

In the US Kraft is protected via tm and cbi.

In the EU Parmigiano-Reggiano is protected via pgs/pdo.

And what of artisanal or small scale cheeses in the US?

What portions of the law are favorable or not to their processes and business?

Like any biotechnology: cheese is as much about the cultural and legal as about the scientific and technological.

Image Sources:

Rollingstone Lavender Chevre

Mt. Townsend Seastack

Rogue Smokey Blue