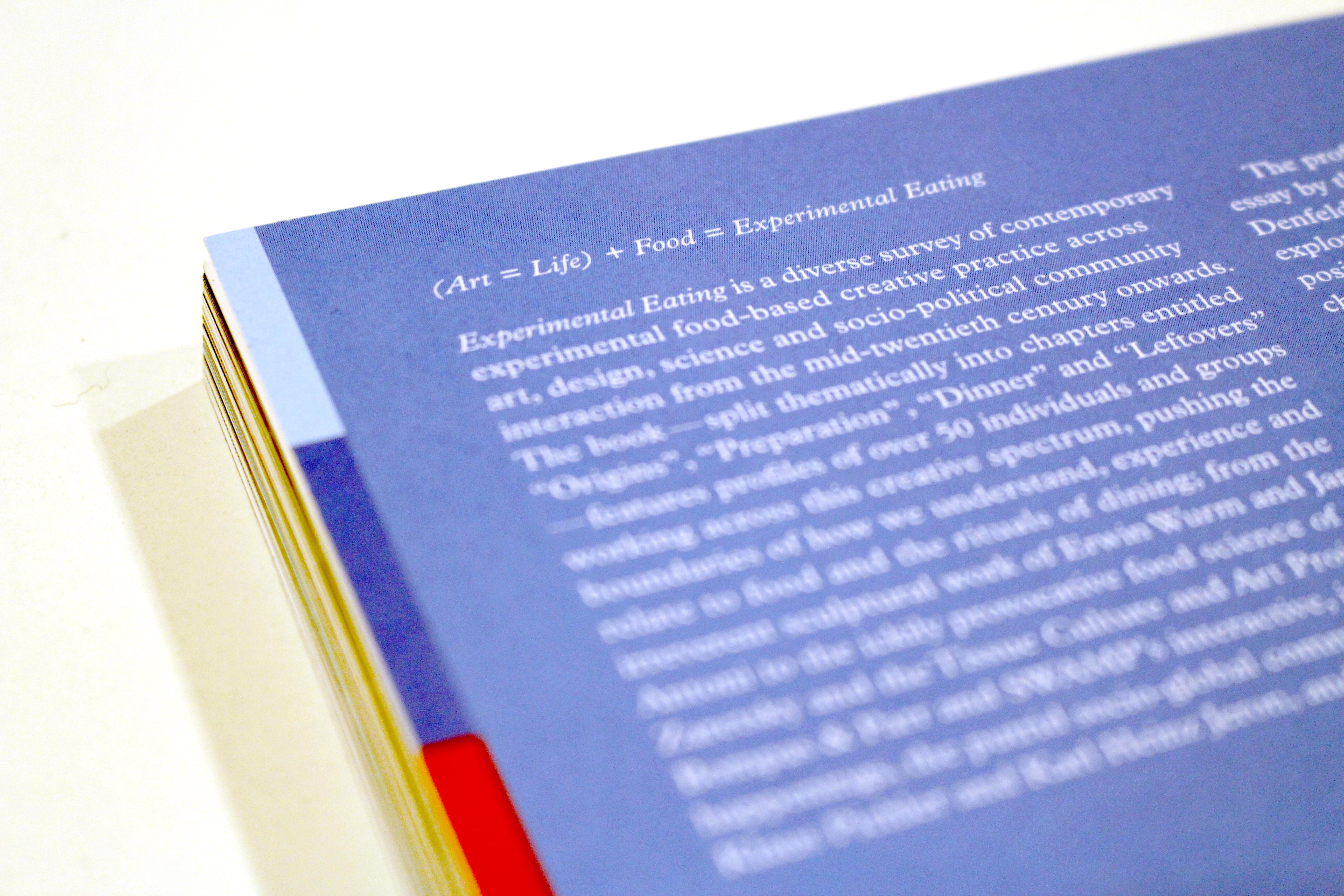

Experimental Eating

purchase book here

Introduction

by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy (Zack Denfeld, Cathrine Kramer, Emma Conley)

INTRODUCTION

This book collects exemplary practices and experiments from the 1960s through to today that deal with gastronomy: the art of preparing and eating food.

One definition of art is making the familiar strange. Nothing is more familiar than eating. Two to three times a day (if you are lucky), you pass a collection of animals, plants, other organisms and minerals (called ‘food’) through a hole in your face. Sometimes by yourself, more often in the company of others. This ritual takes place just about every single day of your life on planet Earth. What could be more familiar?

The artists featured in Experimental Eating insert themselves between the eater and the food in order to create a novel or unusual experience. During experimental eating the audience is thrown off balance, and needs to pay attention. Non-normative ingredients, experiences and etiquette are employed. Things taste, look, smell, feel and sound different to usual.

Experimental eating is an opportunity to document the unusual food rituals humans repeatedly perform or to reimagine the entire act of eating. The practices in this book embrace other ways of consuming and explode the assumption that there is a correct way to eat. The desires of the artists are as varied as the food they depict or serve, but because everyone seems to have an opinion about food, these practices tend to be more immediately accessible than many manifestations of contemporary art. Art is a sensory experience, and experimental eating adds layers of smell, taste and texture to the visual stimulation that still dominate contemporary art practice.

Some artists create art about gastronomy and the food system, while others use food as a Trojan horse in order to address related or even tangential topics. If you dig deep enough, food is about farming, biology, ecology and Earth science. However, with a focus on eating, most of the works in this book pick up at the farmers market or supermarket and end with digestion. Experimental eating primarily takes place in the kitchen, at the dining table and during a meal. Agriculture and gastronomy are inseparable, but experimental eating focuses primarily on the second half of this equation. Art about eating is nothing new, but this book generally focuses on a range of cultural practices that have only emerged in the last 50 years.

(ART = LIFE) + FOOD = EXPERIMENTAL EATING

From sixteenth-century still lifes to Futurist cookbooks, food and art have a long and entangled history; but the work collected in this book generally begins in the 1960s for a reason. Many of the projects featured in Experimental Eating—and our own work as the Center for Genomic Gastronomy—take inspiration from the post-studio art practices that came to the fore in the 1960s and 1970s. Post-studio artists wanted to decrease the distance between art and life. Sometimes they wanted to make work that was immediate and not mediated; to work collectively, share their work outside of the museum and gallery system, and create experiences that took place in real-time or were ephemeral. Many post-studio approaches to art were more haptic than optic. They involved assembling people, artifacts and organisms in novel configurations.

Artists such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Peter Fend and Agnes Denes (to take an arbitrary cross-section from New York) pushed art practice so far outside of the act of image creation, that it became unclear if what they did could even be called art. A following generation of collectives like the Critical Art Ensemble, the Institute for Applied Autonomy, the Center for Land Use Interpretation and the Bureau of Inverse Technology experimented with organisational aesthetics and freely employed both technological mediation and performative immediacy as the circumstances required. In order to create their interdisciplinary artworks these groups identified specialist collaborators or acquired skills in non-art domains such as robotics, digital cartography or the life sciences. These collective practices from the 1990s to the 2000s moved fluidly between interactions on the street, exhibitions in the sanctioned art world and engagements with specialists in the halls of academia and research institutions.

The Center for Genomic Gastronomy and many of our peers who research food have been drawn to the strategies of post-studio practice and artists’ collectives. Preparing and serving food, or intervening in networks of food production and consumption, are logical starting points if your goal is to make art that takes place in real life and in real-time. Experimental eating is an opportunity for the artist and their audience to get away from the glowing screens that increasingly dominate our lives. Food reconnects us with our immediate surroundings and creates a frame for real-time interaction uninterrupted by needy digital devices. Ingredients are derived from living organisms and make visible the flow of biomass through our contemporary economic system. Ingredients rot and release aromatics when they are heated. They call attention to themselves through multiple human senses. Artists can transform raw ingredients into artistic works, but food doesn’t stick around long enough to be easily collected by museums. The flavours and smells of food are a direct and immediate language for artists to communicate with, but the required labour and cost of ingredients needed to create novel food experiences guarantees that the audience for live experimental eating will be small but sensually engaged, and the production will be a collective effort. Experimental eating is rarely the act of a lone genius. Images or representations of food (part of the experimental eating canon) have a slightly longer shelf life, and can be reproduced and recuperated with more ease, but the experience of an audience-who-eats is bounded by time and place.

Some of the lineages of post-studio art that involve food production are mapped out in this book. In 1971, Gordon Matta Clark helped found FOOD; a conceptual, but functioning restaurant, managed and staffed by artists. Sitting somewhere between a small business and artist hang out, FOOD produced performances, ephemera and more often than not, food that could actually be purchased and eaten. FOOD sets the stage for a range of practices in this book that sit provocatively between conceptual performance art and commerce. Some projects are one-off meals, while others are ongoing supper clubs, pop-up restaurants and even long-established food carts that serve food to regular customers. Neither FOOD or its contemporary progeny are profit-making but they do demonstrate the ability of artists to wear the camouflage of everyday life and exist within an economy of food service, even if temporarily. Now we move from unsuspecting audiences to unexpected guests.

DOCUMENTING & EXPLANATORY MODELS

At the other end of the spectrum from art that seeks to exist in real time and real life are artists who use the documentary and archival potential of art to tell stories or examine systems. These food stories may fall between the cracks of journalism and history, or are best told using combinations of image, object and text. Some artists document aspects of the food system in order to establish a new point of a view or to trace a journey, helping the viewer witness and understand the human food system as it really is. Artworks in the documentary mode in this book include Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren den Haan’s Monument of Sugar—how to use artistic means to elude trade barriers, 2007, and Gerco de Ruijter’s Crops, 2012. These artists take advantage of forms such as filmmaking, image collections and digital archives in order to create databases that can be added to over time or re-instantiated depending on the exhibition context or means of dissemination. These works often have a didactic or diagrammatic purpose, but in other cases the voice is more personal and subjective.

The real question is: Do you really want to know how your sausage is made? Whereas industrial food producers and the majority of restaurants work hard to hide the process of food production from the eater, experimental eating is an opportunity to document the journey and preparation process of food. Although the act of eating is familiar to every human, eaters across the planet are increasingly alienated from the production of food.

The Mutato Project, 2006–, is a photographic collection and online archive of raw fruits and vegetables that documents the botanical anomalies in shape, size and colour that cause individual plants to be excluded from supermarkets. These are the most humble of ingredients. They only look fantastical because most eaters are accustomed to being confronted with standardised and curated fruits and vegetables that reach the market from the field. Europe and America both engage in a gastronomical culling: either a bureaucrat decides what botanical deformities are unacceptable or someone in marketing does. Either way, perfectly edible and nutritious fruits that don’t conform to those standards are thrown away, or sent to second tier outlets. The Mutato Project archives these outcasts, and lets us in on an unseen side of food production.

At the Center for Genomic Gastronomy we have recently been documenting the history of mutation breeding, in particular radiation breeding—the process of exposing plants and seeds to chemicals or radiation in order to cause random mutations. Mutation breeding is an agricultural technology that has proliferated globally since the end of the Second World War. For over 60 years, scientists on six continents have been exposing plants and seeds to radiation and chemicals in order to induce mutations. Like many newly developed technologies, especially those promulgated directly after the Second World War, mutation breeding was touted as a technological solution to complex social problems such as global hunger.

Our Cobalt-60 Sauce, 2013, is one instantiation of this research: a barbecue sauce made from mutation-bred ingredients featuring radiation-bred ingredients such as: Rio Red Grapefruit, Milns Golden Promise Barley and Todd’s Mitcham Peppermint. In order to create the sauce we had to identify, source and assemble commercially available mutation-bred plants. More than 2,500 mutant crop varieties have been registered with the United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency, but they are not labelled on store shelves, and identifying the provenance of mutation-bred varieties requires reading primary source documents, news articles and even historical advertising copy. These curious cultivars populate our human food systems and sit anonymously on our supermarket shelves.

When served publicly, the Cobalt-60 Sauce creates a frame for asking questions about the mutation-bred ingredients that are being served, and for elaborating on the similarities and differences between the history of mutation-bred crops and contemporary controversies surrounding genetically modified crops. Sixty years after the launch of mutation breeding programmes around the world, the initial hype surrounding the technology has worn off, and fears about possible human and environmental health consequences have similarly diminished. Cobalt-60 Sauce is a project in the documentary mode that seeks to highlight a forgotten history and connect it to the controversies and debates of today.

INVITING OTHERS

Eating often takes place during an event called a “meal”. A meal is an organised practice that draws on a body of rituals and tools, has a pre-planned menu and a set number of invited eaters. Meals usually involve friends, family members or people who are connected through kinship networks. Only rarely do we dine with complete strangers. It would be peculiar for you to show up at a family picnic in a public park and expect to be fed if you had never met the other diners—it is annoying to picnickers when ants crawl on their blankets or bees land on their food. But meals are permeable things and uninvited human and nonhuman guests do show up from time to time.

Experimental eating expands on the everyday guest list. Animals, microorganisms, and human guests from opposing sides of a political conflict don’t usually sit down to dine together, but the meals in this book take into account the excluded, or intentionally invite the Other.

Hosting a meal can be a tricky negotiation process. Some guests may begin conversations that are uncomfortable for the other eaters. A good host doesn’t want to enable unnecessary conflict, but experimental eaters may very well be interested in debating taboo topics while dining. Food is a starting point for conversation. Breaking bread can break the ice.

For example, Jon Rubin’s Conflict Kitchen, 2010–, “serves cuisine from countries with which the United States is in conflict” and compliments meals with events and performances that spark conversations not had in public, much less in the polite dining rooms of the United States of America. Trespass the Salt, 2011, by Larissa Sansour and Youmna Chlala unites the neighbouring countries of Palestine and Lebanon by hosting a meal between the two locations, in virtual space. The viewer of this video installation witnesses the dinner between guests on either side of political boundary. Even being exposed to the cuisine and eating habits of the Other is a starting point for establishing familiarity, humanity and for asking new kinds of questions.

It is slightly more difficult to keep out unwanted non-human guests than human diners. Ants, flies, mould and fungus just don’t take no for an answer. We usually cope by attempting to not picture them while we are eating. We don’t conjure up images of pigs while consuming bacon, nor envision the life cycle Penicillium roqueforti when eating blue cheese. Whenever we make images in our heads or in the world, we leave some things out. Images of meals are necessarily constrained. Not every organism or ingredient is accounted for. For example, it is difficult for humans to see and acknowledge the massive number of the microorganisms that predigest their food or the microorganisms that live on and in their body. The numbers are too large, and the organisms are too small.

And although we love to eat fermented food, we tend not to identify by name the bacteria or yeasts that make the food desirable. It’s not generally considered good manners to remind everyone that the act of human eating inevitably involves the death of nonhumans. Klaus Pichler’s One Third, 2011–2012, is a series of carefully staged photographs of rotting foodstuffs that make us wretch whenever we see them. Images of decomposing food are a reminder that our food consists of and is inhabited by organisms; images and sculptures of decomposing food whisper “It is inevitable that your food will die. (And you will too.)”

What about nonhuman diners that are closer to our size? Some families feed their pets at the same time as they themselves eat, but mostly the nonhumans that exist in our environment are not invited to dinner. In order to correct this omission, in 2011 the Kultivator collective from Sweden created a meal that could be eaten by both humans and cows simultaneously. Natalie Jeremijenko’s Cross Species Adventures Club is an ongoing event which includes dishes that are nutritious, tasty and beneficial for both human diners, insects, fish and other organisms. Marina Zurkow’s 2012 happening Not an Artichoke, Nor from Jerusalem was a dinner where native and invasive species are harvested and served. These experimental meals ask us to consider who and what belongs, extending our ability to envision what is difficult to see, or to invite difficult guests.

Finally there are the uninvited guests of contaminants and pollutants that exist in our food and in the environment around us. Air, water and soil pollution enter our foods and our bodies, often shaping the flavour and nutrition of the food we consume. The Center for Genomic Gastronomy’s Smog Tasting, 2011, is a research project that makes the invisible ingredient of smog both visible and tastable; the research takes the form of egg-whipping performances and the production of recipes. During the performances, egg whites are whipped in various outdoor environments in order to harvest air pollution. Whipping eggs creates egg foams, which are up to 90 per cent air. Particulate matter and other airborne pollutants get trapped in the batter. Smog from different locations can be served, tasted and compared in the form of polluted meringues.

Smog Tasting has also been served in less polluted geographies, where a more metaphoric approach has been taken. Quantitative air pollution data from the local site and from cities around the world are translated into a collection of recipes with simulated pollutants, so that participants can taste differences in air quality. Quantitative data is most often visualised or sonified, but the Smog Tasting creates an opportunity to use smell and taste to interact with data.

From a culinary perspective, environmental pollutants are unwanted ingredients in the human diet. Taking into account the presence, flavour and nutritional impact of these invisible ingredients is one method of experimental eating. Making meringues at traffic intersections and on rooftops looks unusual and tends to draw a crowd. Conducting the Smog Tasting in public is a frame for asking questions about the relationship between food, the environment and our body, and seek answers collectively.

SITE AND SPECTACLE

Where should we eat? What should it feel like? What if getting food into your mouth required the assistance and co-operation of your fellow diners? The following projects experiment with the where and how of eating. Marije Vogelzang’s Sharing Dinner, 2005, ties strangers to a tablecloth and their every move shifts the configuration of the table. Each diner is required to share ingredients in order to complete a dish, and must engage in a complex dance of collaboration and consumption.*

The same food tastes very different if it is eaten al fresco, on a tree-lined avenue or underground, in a former missile silo. Our attention and senses are modulated based on the architecture or environment we find ourselves in. Environmental aspects such as light, air quality and temperature set the mood. Putting eaters in a novel setting or constraining their movements ensures that they will be in the moment and paying attention in a way they would not in their own home or a familiar restaurant.

The temporary Ridley’s Restaurant, devised by the Decorators and Atelier ChanChan in 2011, not only raised diners well off the ground, in an unusual urban location, but also replaced the dumbwaiter with an entire dining table that could be raised and lowered between floors. Throughout the dinner the architecture of the meal was reconfigured, and the flow of conversation and consumption was disrupted.

Between the act of entering an architectural space and food finally reaching your stomach there are a set of tools, garments and utensils required to perform the act of eating. Soup spoon, gravy boat, oyster knife, spork. Bib, napkin, deep fryer, drinking straw. Artists who disrupt the tools of the meal, disrupt the patterns of our body in space and time.

SWAMP’s Meat Helmet is a tool that forces the eater to overstay their welcome. After typing in the number calories contained in your McDonald’s Big Mac (560), the Meat Helmet forces the eater to continue chewing until they have burned off all of the calories they just consumed. Watching a diner with a cybernetic eating-helmet for eight hours in a McDonald’s causes a counter spectacle to the colourful advertising and interiors of the McDonald’s chain. SWAMP has conducted other studies of work atmospheres and material production by living and eating in a single WalMart for 24 hours and by continuously looping around a McDonald’s drive through, buying and consuming a single item at a time.

As part of our research into mutation breeding the Center for Genomic Gastronomy has experimented with vortex cannons as a means of delivering clouds of mutation-bred peppermint oil. Most eaters have fun releasing puffs of atomised liquid into the air, but are slightly more hesitant when they learn about the history of the ingredient they are letting float around the room and into their mouths. The spectacle of humans making small green mushroom clouds and licking the air is just one of the spectacles that are created by modifying the tools, spaces and architectures of eating.

DECADENCE FOR ALL

Experimental eating has an uneasy relationship with abundance, excess and inclusiveness; it often feels more like a celebration or a special occasion, rather than something one would do everyday. Some artists riff on the potential for spectacle and decadence inherent in banquets while others decontextualise ingredients that are mundane or a humble in order to consider them in a new way.

Displaying large quantities of expensive food is still one of the ways that societal elites communicate their wealth or power. Exotic ingredients and flavours indicate that an elite has the access, knowledge and the wealth to acquire ingredients from far off places, and compose them into something that is satisfying to eat. Sometimes just sheer quantity is enough to show off. Jennifer Rubell’s Icons, 2010, draws on art historical references to put on a banquet in a gallery. Piles of meat, vegetables and junk food, champagne fountains and spigots of alcoholic beverages are installed throughout the museum; this is the decadence of a post-sixteenth-century still life painting that has jumped out of the painting so it can actually be consumed.

Should truly decadent experiences only remain within reach of the privileged few? Is universal access to hedonism and pleasure a goal worth fighting for? Industrialisation and Fordism paved the way for optimisation and standardisation, strategies that have significant consequences when applied to food systems at a planetary scale. Can experimental eating prototype universal access to pleasure through food?

Bompass and Parr have an oblique take on decadence and abundance. They have employed the garish colours and the lovely wobble of jelly (Jell-O to Americans) to create spectacular sculptures. Their work often utilises food products that are highly processed, commercially branded and vilified by foodies. For the Heinz Beanz Flavour Experience they matched five flavours of baked beans with handmade bowls and audio-emitting spoons. Their work builds on the detached celebration of industrial food culture typified by Andy Warhol and his famous quote, “A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.”

Taking a much more critical approach to industrial food culture, Paul McCarthy has employed bottles of ketchup and chocolate syrup as stand-ins for bodily fluids in much of his work. The recontextualisation of these ubiquitous condiments transforms the everyday into the grotesque, and creates images that have the power to disturb.

Moving away from the packaged uniformity of industrial food, Carl Disalvo’s collaborative work is explicitly process-based and engages in the hands on co-creation of food with an audience. Projects such as GrowBot Garden, Food Data Hacks and Kitchen Lab combine food, technology and community in order to generate locally specific cultural expression and instigate social action. These projects have attempted to create space for co-creation between amateurs and experts with various domain expertise. An organic farmer drawing on their own experience in the field likely has very different insights about potential use for agricultural robots compared to an electrical engineer.

Finally, our own Vegan Ortolan, 2012—, is an on going cooking contest to make the best vegan simulation of the cruelest meat dish ever invented: the Ortolan. The sheer number of ingredients and skills needed to simulate the bones, organs and flesh of a small bird is enormous. Making this simulation a truly delicious experience is even more difficult. This project appears to be a form of culinary absurdism, but the process is also a form of cultural exorcism that allows the novel culinary culture of veganism to replace animal cruelty with culinary complexity and abundance.

THREE MODES OF SPECULATIVE GASTRONOMY

In order to succeed, novel food movements need to be beautiful, delicious and open to experimentation, and one branch of experimental eating that this book explores is speculative gastronomy, which employs the tools, symbols and processes of food preparation in order to imagine food futures, prototype alternative cuisines or critique existing culinary practices.

Part of our role at the Center for Genomic Gastronomy is conducting workshops that train creative practitioners, food professionals and amateurs to imagine and test a range of food futures. Sometimes this involves the creation and dissemination of images and mock-ups. Other times prototyping the future demands the procurement of edible organisms and chemicals.

There are at least three approaches to asking “What if?” in relation to food: diegetic, figurative and realist. Diegetic speculative gastronomy involves the creation of props and images of food. Figurative speculative gastronomy consists of metaphors that you can eat. Realist speculative gastronomy is the thing itself, not metaphors; foods from the future that can be served to human eaters, today.

Speculative gastronomy practice exists all along this continuum, but it may be useful to use these three approaches as points on the map, and to draw on examples from this book relating to InVitro meat to illustrate each approach. InVitro meat—animals cells grown in a lab for the purpose of human consumption—is interesting because it is a cutting edge technology that has been dreamed about for decades, but was realised and presented in public by artists as well as scientists. Since the serving of the first lab-grown meat by the Tissue Culture and Art Project, artists have continued to envision, critique and debate InVitro meat.

An example of diegetic speculative gastronomy is Dressing the Meat of Tomorrow by James King, 2006: a project that imagines one way InVitro meat might look, taste and be served if, or when, it leaves the lab research phase and is put into commercial production. The piece is exhibited as a plastisol sculpture and a short text, through which the viewer is provided with minimal context about the technology of InVitro meat. The diegetic prototype is a prop constructed to complete a fictional story that the audience can view and discuss, omitting any of the actual biological materials involved in InVitro meat production.

A photograph of the sculpture and text related to the piece has been remediated in various forms on the Internet—the iconic imagery and fantastical narratives make this kind of work ideal for dissemination and debate on such a medium—and continue the conversation and debate beyond the confines of the gallery where the piece was exhibited.

The diegetic approach allows the artist to express something about food, or the future, without being constrained by material reality, the laws of physics or biology. By creating artefacts and fictions that present a plausible and well-articulated future reality, audience members can imagine themselves inhabiting a fiction, casting themselves as an actor and thinking through the implications. However the audience is not given access to or allowed to eat diegetic prototypes—food which is unsafe, inedible or can only be simulated, as it simply doesn’t exist in biological/material form.

One historical example of diegetic speculative gastronomy is the pill food that featured in fiction and film throughout the twentieth century: abstract little pills promised everything from the flavour experience of an entire five-course meal to your complete nutritional needs for an entire week. Although no one has ever successfully created or sold pill food that delivers on those imagined possibilities, we now live in a world of ready meals, meal replacements and molecular gastronomy. Pill foods were used as props in films to express excitement about scientific advancement or horror at the alienation inherent in technological progress—different viewers might interpret these food props in either way depending on their own assumptions. But the image of the pill food, the context it was pictured in and the performance of a human actor consuming it all helped build the vision and cue viewers to think through the implications of technological advancement.

Figurative speculative gastronomy involves the creation of food that can be consumed by humans, though it need not taste good or be nutritious. In the figurative mode audience members move from viewers to active participants. They are pushed beyond commenting on a future scenario in the abstract, and are confronted with the reality of consuming and incorporating into their body something unusual or uncomfortable.

While it shares many qualities with diegetic work, in Figurative speculative gastronomy more emphasis is placed on the experiential, haptic and edible aspects of the fiction that is being conjured up. Figurative creations can combine images, media, sculpture and performance, but what sets them apart is their use of food that can be consumed.

ArtMeatFlesh is a series of performances by Oron Catts and the Center for Genomic Gastronomy that have taken place in three countries since 2012. During these live cooking events, two teams composed of artists, scientists, philosophers and chefs compete in a kitchen where they create dishes for a live studio audience to taste and judge. Each dish addresses one aspect of InVitro meat or the future of protein production and consumption. Although no actual InVitro meat has been served at ArtMeatFlesh events, the ingredients used have included products such as fetal bovine serum (FBS) and horse serum, which are used in the lab during the creation of InVitro meat. Members of the audience have to decide whether they feel comfortable eating these ingredients after learning about their ethical, ecological and health consequences. Often people who initially feel willing (or not) to eat something change their mind when they are able to experience the sight, smell and sound of the food before tasting it.

In a similar vein, discussions about converting to an insect diet are very different when an audience is shown seductive images of imagined insect sausages or when they are actually presented with real cooked grasshoppers or ants.

REALISM IN SPECULATIVE GASTRONOMY

The Tissue Culture and Arts Project also presents an example of realism in speculative gastronomy—like that of producing and serving actual insect sausages—via their ongoing work on InVitro meat. In order to create and serve their project Disembodied Cuisine, 2000–2001, the artists spent many years working in life science labs to acquire the skills needed to conduct tissue engineering and create a piece of disembodied animal tissue that could be served as food. In order to serve this novel food, the artists had to go beyond exploring the ethical, legal and cultural constraints of InVitro meat; they had to fill out the paperwork and conduct due diligence as well as provide a conceptual and physical context for the meal to take place in a safe and legal fashion.

The realistic approach to speculative gastronomy prides itself on generating material instantiations that go beyond metaphors. By seeking out novel ingredients, biotechnologies and cooking processes, and by serving them to an audience, realism implicates the eater directly in the imagined alternative food culture. These experiences remain experiments and are not necessarily repeated, or may not scale well for commercial or even artistic purposes, but can open up new pathways for receiving direct feedback from eaters.

Many artists oscillate back and forth between these modes depending on the circumstances and the questions they are interested in. For example, artist John O’Shea explores our relationship to animals and the ethics of meat consumption across all three modes. His ongoing project the Meat License Proposal aims to a pass a law in Great Britain requiring every meat eater to slaughter an animal at least once, and the artwork documents his investigation into the legal process of proposing such a law. The project is diegetic speculation, but grounded in a concrete understanding and exploration of the legal framework of the UK. His Black Market Pudding project proposes an ethically conscious food product (black pudding made with blood from a living pig), which has been served and eaten, but not yet bought and sold commercially.

Similarly, Sissell Tolaas and Christina Agapakis’ Self Made, 2013, sits between modes of speculative gastronomy. The artists created cheeses with starter cultures isolated from the hands, feet, noses, and armpits of artists, scientists and cheesemakers. However, they do not publicly serve the cheese as food. This work seems to exist between the world of diegetic prop making and the creation of a novel foodstuff that can be served to participants who are willing to eat it. Each of the three modes of speculative gastronomy are excellent tools for asking questions, but each comes with its own affordances and limitations.

EATING AHEAD: TOWARDS A CRITICAL APPROACH TO EXPERIMENTAL EATING

Something big is happening in the world of food, across the entire planet, and we need the voices of artists, outsiders and experimental eaters to make sure that we collectively build a food system that is more just, beautiful and biodiverse than the one we currently have.

Experimental Eating is an essential collection because seemingly everyone is interested in the topic of food. Mainstream media outlets cover celebrity chefs and food culture like never before and there has been a massive growth in specialised media covering every aspect of food culture. It is cool to cook. On the other hand, academics and policymakers fret over the ecological and economic implications of our ever-growing human food systems. There are more mouths to feed, increasing inequality and the same amount of land. Will we be able to feed everyone? How do we move away from non-renewable resources as they become scarce? Resource constraints and food insecurity are being examined from both and agricultural and a culinary angle. Finally, trend forecasters, social engineers and venture capitalists are looking all over for inspiration to create new products, increase profits and cause creative disruption.

Since the establishment of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy in 2010 we have been sharing many of the projects and practices contained in this book with students, collaborators and colleagues. One way we plan to use the Experimental Eating book in our own practice, is as a conversation starter with people who think deeply about food cultures and food systems, but not necessarily about art. Even audiences that are sceptical about the purpose or significance of contemporary art pay attention when food is involved. Whether these audiences recognise it or not, contemporary art is an essential domain of experimentation and research because art still makes room for unpopular views, freedom of expression and non-instrumental research. Few other disciplines can compete on these aspects. Discussions around the current global food system are obsessed with increasing yield and efficiency, often ignoring biodiversity and resilience. As humankind goes about reinventing the global food systems it is important to consider the beauty, complexity or criticality in these projects and how that could translate into non-art domains. These projects are a good starting point for everyone who wants to experiment with eating.